I thought I would share the workflow I use for managing Final Cut Pro X Libraries, Events and Projects. Having an organised and methodical system really helps to keep on top of the huge number of video, audio and other files that video-making generates.

Unfortunately, like many of us new to FCPX or other video NLE’s, I didn’t have a system and ended up with media all over the place, every project handled differently, and never really knew where or what anything was for or how I had used it.

Disclaimer: This is not “the best” method, just one that works for me, which has made file management much easier and improved my productivity.

I now have a logical organisation for each FCPX project and its associated media files, thanks to me finally understanding three important points about how FCPX Libraries and Events work.

FCPX Libraries

Libraries in FCPX can be stored anywhere on your system, and we can have as many Libraries as we need for managing our projects. An early rookie mistake I made was to use one Library for everything. A single Library becomes huge, unmanageable, slows down the computer, and finding stuff becomes a headache.

FCPX Events

FCPX Events make more sense when we think of them as special types of folders, rather than “events” in the traditional sense. This means we can create as many Events as we need within the Library, for managing the different types of media we may be handling in our project. (Note: when I mention “project” in lowercase, I mean the “thing” we’re making, be it a video, film, etc, not to be confused with FCPX’s Projects, which mean something specific in the context of FCPX.)

Leave media in place or save it in the Library?

When it comes to media handling, FCPX can work in one of two ways (or a mix of both): either we can import media into the Library, so that it physically becomes part of the Library file, or we can leave it in our computer’s folder structure in whatever way that makes sense to us and just tell FCPX where it is. We can do either, or both – whatever makes sense for us. Having a consistent approach to whether or not files are physically stored in the Library really helps media management.

Let’s look at the steps I go through each time I create a new FCPX project.

1. Setting up the folders on my hard drive

I think this is key. Get this right, ie by using a consistent structure of folders for projects, and half the battle is won.

All my projects are stored in a “_PROJECTS” folder on my external hard drive, with a sub-folder for each “project”. I use a strict naming convention for these folders, comprising the date of the shoot (plus an index number if more than one shoot on the same day, which is rare) and some keywords to help me know which project I’m looking at, usually the artist and abbreviated song title.

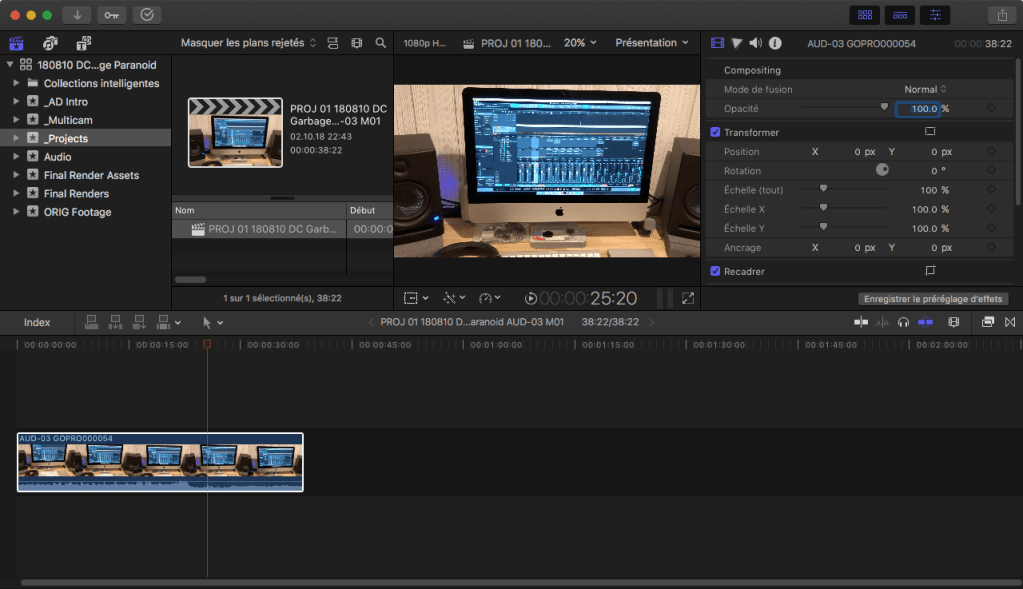

Here you can see three projects, all shot in 2018. The “DC” in the filename is just to remind me that this is a drum cover, the rest of the name is pretty self-explanatory.

Within each of these “project” folders I create various sub-folders for holding the media related to that project.

Folder structure within each project folder:

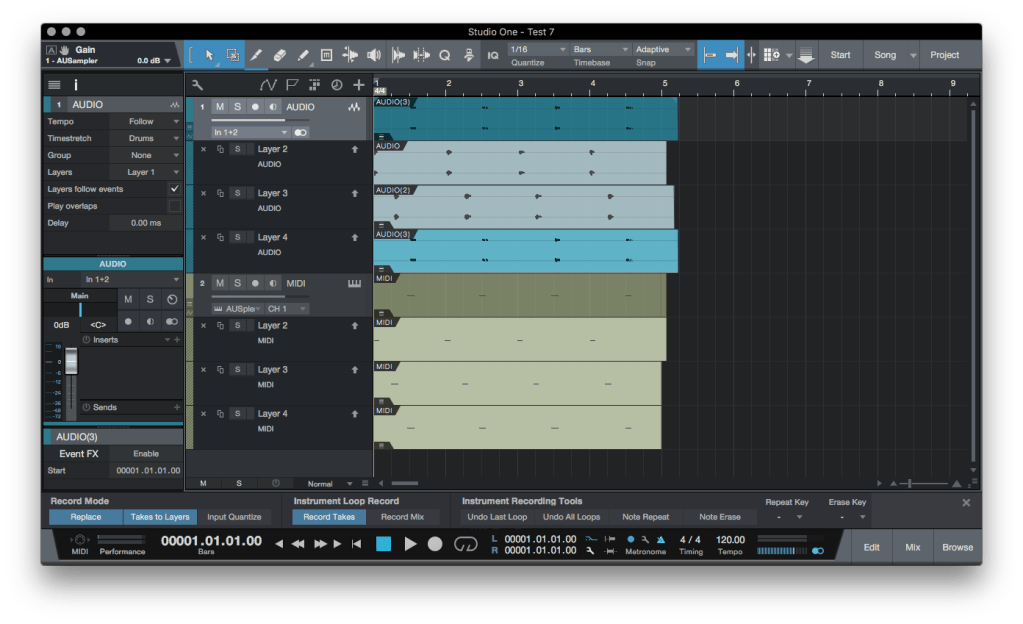

- Audio – For the final audio mixes created in Presonus Studio One.

- Final Render Assets – For all other media, other than video and the final audio, related to the project. For example, the screengrab I will use for the video thumbnail, its associated Photoshop file, and any other stills and logos that I may use.

- Final Renders – Contains the final renders exported from FCPX for publication.

- ORIG Footage – This where I import all video files directly from my cameras, using the OSX Image Transfer utility. There are sub-folders within this folder, one for each camera used on the shoot.

- ORIG Footage Not Used – I use this for temporarily storing the videos of takes I won’t work on (due to a playing mistake or other issue). These are not imported into FCPX, and are kept purely “just in case”. Usually, once I’ve finished the project and rendered the final files, I delete everything in this folder as I will never use these files.

2. Offloading media from the cameras

Now that the project folder and its sub-folders have been set up, I can import the video files from the cameras using Image Transfer. (Importing to FCPX will come later.)

As mentioned, each camera gets its own folder within the ORIG Footage folder. This is very handy when we come to importing into FCPX, as FCPX will use the camera folder name to automatically create a keyword within the Event the media has been imported to. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

By using Image Transfer, rather than offloading via FCPX, I can review the footage before deciding which take I’m going to keep, and also rename all the files so that I know what is what. As I generally shoot a drum cover with multiple cameras, I need to keep track of which video files go with which audio take. How I organise audio takes in Studio One is a subject for another article, so I won’t go into details, other than to say that each take will be named “AUD-01”, “AUD-02”, etc. I like to prefix the video filename with the audio take number, which is helpful once the video files are imported into FCPX, as video files related to the same audio take will appear together in the file list in the FCPX Browser window.

Unwanted takes are moved to the ORIG Footage – Do not use folder, for deletion once the project is finished. In other words, only the video files for the best take will stay in the ORIG Footage folder.

At this stage I will also track down any other media I need and move these files to the Final Render Assets folder. Typically, this will be the Photoshop file I use for creating the Youtube thumbnail. I will also FCPX screen grabs to this folder. The final audio mix files created in Studio One will be saved in the Audio sub-folder.

3. Creating the FCPX Library

Now that all the media is where I want it on the hard drive, the next step is to open up FCPX and create a new Library.

I name the Library the same as the project folder (eg “180810 DC Garbage Paranoid”), and save it in the root of the project folder. I use one FCPX Library per project, and save each Library in its relevant project folder.

The beauty of this is that I now have everything in one place on my hard drive, so can easily backup or archive the entire project to another drive by copying the project sub-folder and its contents. This means that each Library and all its media are self-contained and I can move them around, transfer them to another machine, or even give them to someone else to work on, etc. Very practical.

4. Creating the FCPX Events

Now the Library is created, I will set up the Events that I use for organising the media within FCPX, using a structure and naming convention that mirrors the hard drive folder structure created previously.

In the screenshot you can see that I’ve created Events with the same names as the folders created earlier. However, as I will not import video files related to bad takes, I don’t create an “ORIG Footage – Do not use” Event as it won’t be of any use to me in FCPX.

To finish off the setting up the Events, I create two additional Events unrelated to the folder structure on the hard drive. The _Projects Event is where I will keep all the FCPX Projects used in this Library. The _Multicam Event is where I keep the Multicam clips that I will create from the raw footage. Why will there be more than one Project and one Multicam? Because I may create subsequent versions of the Project, or decide to work on more than one take, so having these dedicated Events is very helpful in keeping things organised.

The AD Intro Event is a special case. I use a short intro clip at the beginning of each video, and this clip was created in FCPX with its own Library. Within this Library I have an Event called AD Intro which contains the final render of this clip. I simply copy this AD Intro event into each new project Library and store the underlying files in the new project Library. This probably sounds more complicated than it really is, so I hope it makes sense. The key plus in doing this is that I can manage the intro clip within FCPX Libraries and don’t have to worry about where to keep the relevant files – they are just copied into the new Library. The only down side is that this does increase the size of the Library and uses up a bit of hard disk space, but the intro clip is short, so this isn’t a big issue.

5. Creating the FCPX Projects

The final stage of setting up the Library is to create a Project so that I can start editing and putting the final film together.

I use a strict naming convention for each Project so that I know which recording take it relates to, together with a version number in case I create several versions of the Project. For example: PROJ 180810 DC Garbage Paranoid AUD-03 v1

AUD-03 tells me that this Project contains footage of recording take #3, and v1 tells me that this is the first version of this Project. If at a later date I decide to re-cut the video, I will create a new version and name it v2, etc.

Why keep Projects in a separate Event?

Usually, FCPX expects Projects to be created within Events. However, they can be kept anywhere within the Library, and as each Library has several Events I prefer to keep them in a dedicated Event where I know I can easily find them. This is the kind of flexibility I really like about Final Cut Pro X.

6. Importing the media into FCPX

The final stage is to open up the FCPX media import window and import the media into the relevant Events.

In another post I will go through my workflow from here through to rendering the final video.